by Rachel Clarke and Claudia Hart

The virtual camera is the gateway to the the virtual world. This geometric, spatial world can only be viewed through the cyborg eye of a virtual camera, which can be seen as another example of a technological grotesque. A hybrid of the same sort of perspectival system developed during the Italian Renaissance and a mathematical computer model, the virtual world merges classicism and Cartesian rationalism, using a grid and a coordinate system to map geometric objects into XYZ space.

The virtual camera in a 3D virtual imaging systems is embedded within the software interface. In such software, the sculptural and architectural world is seen only through different viewing portals. Each portal is framed by controls identical to that of either an analog or a digital camera, including depth of field, f-stop, and lens size that can be fluidly shifted from macro to wide-angle or any dimension. The virtual camera can do what the analog camera can do, and much more. It is not constrained by worldly restrictions, meaning the actual physics of optics, or the physical limits of a lens or a space or form. It can be inside objects, and can look or travel through objects. Once a user has created the architectural Cartesian world behind the camera, this world can only be output by "photographing" it or, to use the language of 3D simulation technology, by "rendering" it, thereby endowing it with the various photographic qualities that the user has proscribed.

So simulation software doubles as a camera interface and proposes a world that can not exist outside of mediation. The virtual space and the cyborg-cinematic eye that records it are conjoined twins, simultaneously constructing and defining the 3D space. This virtual world fused with the cinematic eye that records it merge together to create a hybrid medium. As a medium, post-photographic simulation is a form of sculpture merged with photography, neither fish nor fowl but unique in itself.

Within the virtual world, one or many cameras can be placed anywhere in any scene, moved along paths and into places that are phenomenologically impossible. A camera can be shifted at any time, representing a sense of multiplicity in which different viewpoints can be recorded simultaneously to permit a "hyper-Cubist" spatial effect that is both realistic yet fragmented. The physical possibilities of focal length, angle of view, and depth of field effects can also be calculated, manipulated, and wildly exaggerated. Any extreme of physical texturing, including reflections of light, either of the virtual world or hybridized with real-world photographic imagery, can be combined and exaggerated beyond what is possible with an analog camera. In addition, the virtual world is a computer model, literally mathematical and pure in a geometric sense, without the flaws and irregularities of the actual. As a result, surface materials appear otherworldly, and can be hyper-glossy or possess of a seamless perfection. A camera can move in such a way that is impossible in the physical world, unconstrained by gravity, space, or form. Impossible cinematography such as recursive loops, ceaseless, fluid or intricate movement, and views that are locked to objects or placed inside physical forms, means that the omnipotent, cyborg-cinematic eye is one without limits that can finally portray a model of the user's mind.

by Pat Reynolds

The subjects of “photography” and what is referred to within the context of this exhibition as “post-photographic simulation” (artworks created, at least in part, through the use of various specialized 3D rendering and animation softwares, but presented as still images, and often made physical through the same printing technologies and techniques used in “traditional” contemporary photographic works) have seen little crossover regarding their institutional and critical reception and presentation within the art world.

Artist, author, and Rhizome founder Mark Tribe applies the term “new media art” to “projects that make use of emerging media technologies and are concerned with the cultural, political, and aesthetic possibilities of these tools,” which he further defines as work operating within the intersection of “Art and Technology and Media art.” It is potentially this self-reflexive preoccupation with the virtual that marks much simulated photography that has lead to its continued categorization among new media works, rather than it being primarily defined as a tangential or sub-categorical photographic form.

The art-historical photographic narrative seems to insist that Photography, in the purest sense of the word, must involve the transmission of “real,” physical light — whether through a lens, or an aperture, or a direct surface-to-surface transfer, or a gridded series or sensors programmed to translate varying intensities of electromagnetic radiation into numerical digital information — into some sort of image or transformed surface. This attachment to the physical is reflected on an institutional level not only within the basic curricula of photography programs at colleges and universities internationally, but also among contemporary art museums and galleries seeking to both define and legitimize cutting-edge and post-photographic practices. MoMA Chief Curator of Photography Quentin Bajac describes the museum’s ongoing New Photography series of exhibitions as encompassing “framed prints, images on screens, commercial books, self-published books, zines, posters, photo-based installations and videos, and site-specific works, and it will continue to present all the different forms that the photographic image can take,” but the exhibition has not (as of its 2015 edition) featured work that overtly utilizes 3D simulation. Similar approaches to identifying the next wave of photographic presentation and production can be seen within the International Center of Photography’s 2014 What Is a Photograph? exhibition, the artists in which, according to its press release, “have … confronted an unexpected revolution in the medium with the rise of digital technology, which has resulted in imaginative reexaminations of the art of analog photography, the new world of digital images, and the hybrid creations of both systems as they come together.” In this case as well, the exhibition, which aimed to trace the evolution of contemporary photography from the 1970s to the present, stopped just short of observable digital simulation in its curated works.

It is tempting to preserve the necessary presence of the physical in defining “true” photographic practices as an ongoing commitment to photography’s purely analog origins. However, the movement toward a fully simulated working environment and suite of tools could also be argued as simply the next in a historically established (and ongoing) series of steps marking photography’s technological evolution. For nearly as long as photography has existed past the point of trial-and-error experimentation, a definitive constant that has remained alongside the presence of physical light has been the photographic apparatus, which also serves as the model for the foundational set of digital tools and parameters embedded within much professional 3D simulation software. Because these pieces of software have been primarily developed over time for advertising, filmmaking, and commercial imaging industries, the user interfaces employed within each program often employ a vocabulary that borrows from the workflows of these sorts of productions. Users, in many cases, must choose a camera with a lens of a defined focal length, and they must place it within the same three-dimensional space as their eventual photographic subject, which must also be lit using a variety of controllable light sources. They define whether or not they want to shoot an uncompressed or compressed image, and after creating an exposure, they can reframe their shot or relight their subject. With the exception of the presence of physical subjects and physical light, this process contains no more artifice than that of the contemporary studio photography shoot, which similarly consists of a defined composition of a chosen model in a customizable space lit by artificial and controllable sources and output as a generic digital file. Even simulated photographic work that eschews the laborious lighting and rendering processes of programs like Maya and Blender, such as Tribe’s own Rare Earth series of landscapes from war video games or Clement Valla’s Postcards From Google Earth, often exists as the product of one of a number of creative motivations often attributed to photographers — archival impulses, seeking a so-called “decisive moment”, recording a time and place in history, et cetera.

The degree to which post-photographic simulation should be considered a form of photography or a distinct new media practice, like many other nontraditional and technologically informed approaches to the medium, will undoubtedly change over time, especially as the interfaces through which artists engage with the technology continue to evolve. The representation of the typical camera system as a means of organizing the 3D workflow is currently a defining element of software like Maya, but it is also tied to present-day computer technologies and the interfaces through which we engage with them. As augmented reality and other new forms of hardware emerge in accessible consumer technologies, the approaches that artists take in the creation and presentation of 3D works will likely shift as well, presumably in a way that will lead to similar discussions of the delineation between traditional and new 3D modes of production.

AES&F

Trailer for The Feast of Trimalchio, 2009

Tim Berresheim

Condition Tidiness. Rude Stage II, 2008

DIASEC

Edition of 3 + 1 EA

70 inch x 94 inch 180 cm x 240 cm

Shamus Clisset

Don Vont, aka the Good (Wood) Indian, in "Full Phantasm V",

2012

C-print

80 x 53.25 inches

Mark Dorf

untitled20, 2013

From the series //_PATH

32”x40”

Archival Pigment Print

Joe Hamilton

Hypergeography, 2011

Claudia Hart

The Process of History, 2016

Adam Hurwitz

Errand, 2013

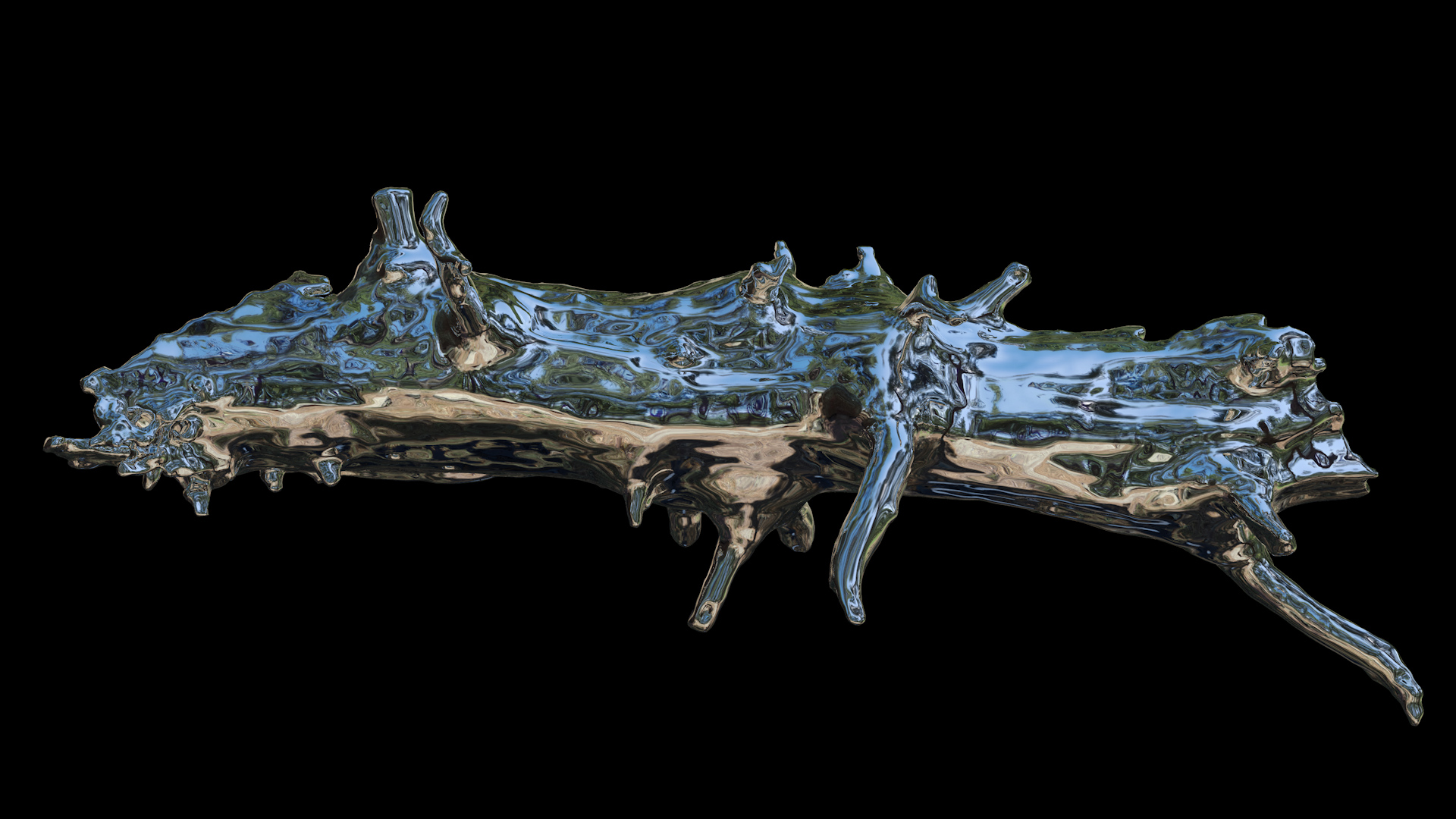

Kim Joon

Blue Fish, 2009

Everett Kane

Untitled, 2014

Christopher Manzione

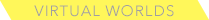

From Only As Beautiful As The Objects It Reflects,

Virtual Sculpture, 2016

Jonathan Monaghan

Mothership, 2013

Shane Mecklenburger

Eternal

Fortune, 2014

Will Pappenheimer

Pulsar Bodies, 2015

Still from on site iPad screenshot video documentation of GPS based augmented reality

Nicole Ruggiero

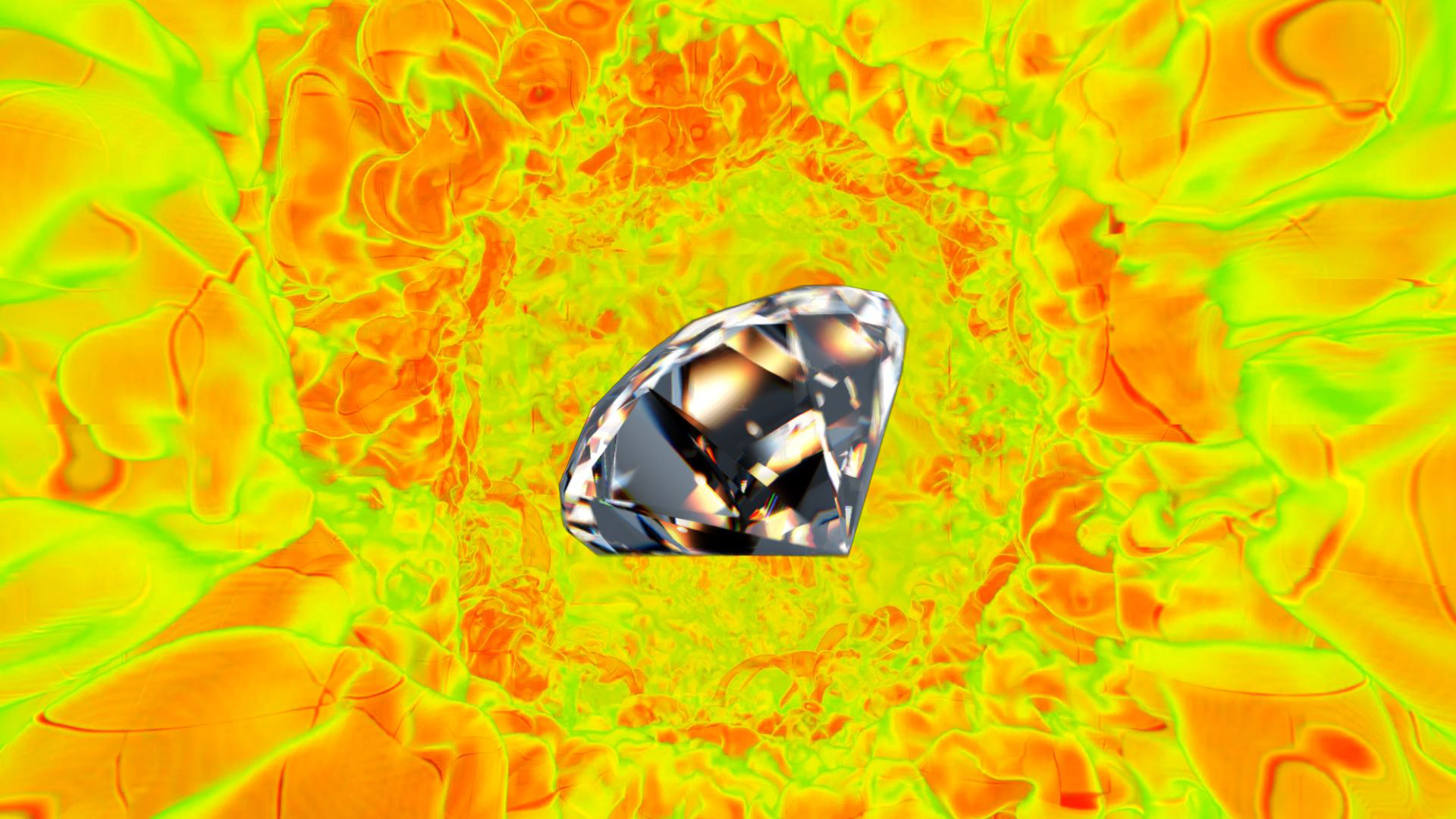

you look at me with this blank

stare...sometimes i wonder if you're even

actually here , 2016

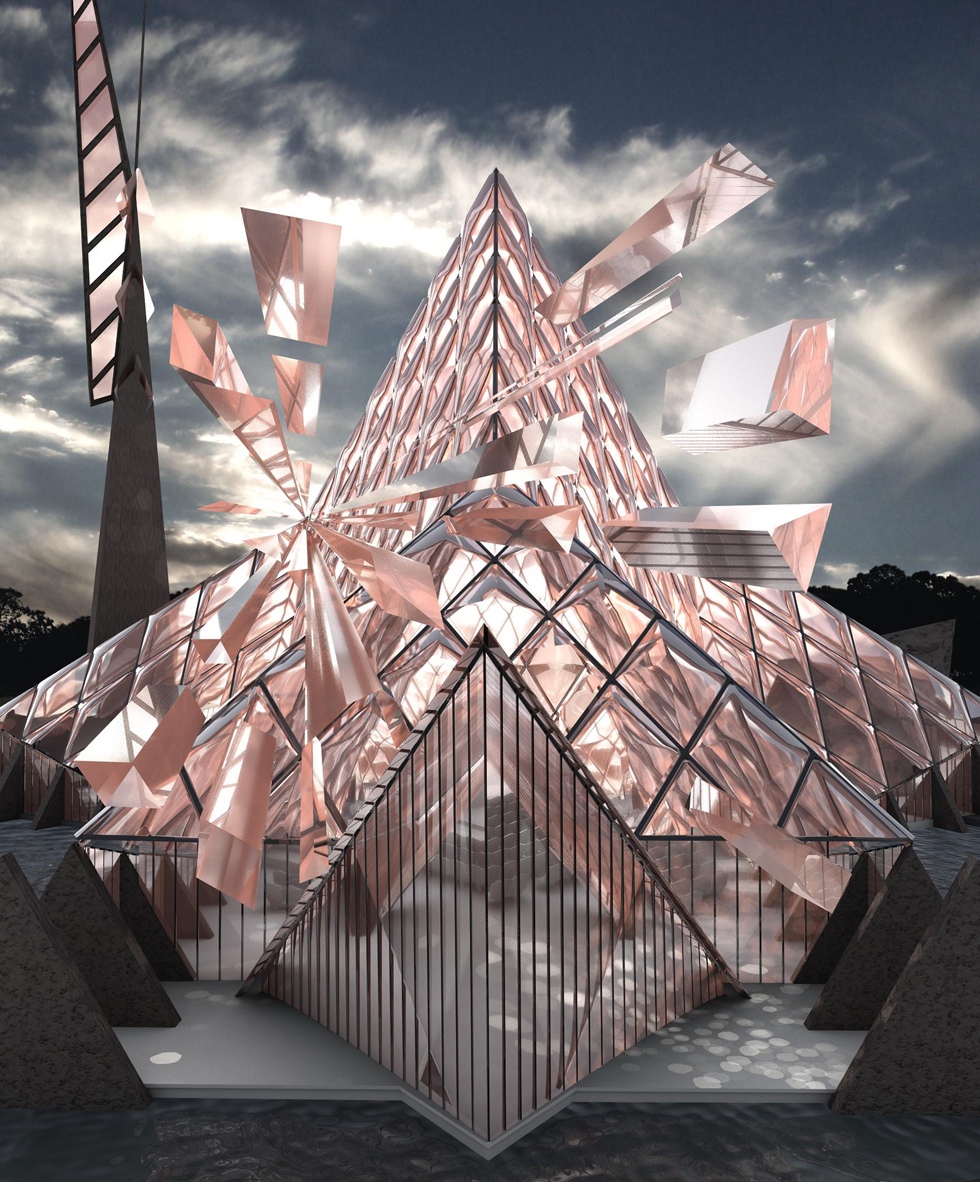

Ellen Sandor and (art)n

Perfect Prisms: Crystal Chapel

This work was inspired by Bruce Goff's designs

and drawings

Virtual Photograph PHSCologram, Video and

Virtual Reality Tour

(art)n

Ellen Sandor

Chris Kemp

Chris day

Ben Carney

Miguel Delgado

Diana Torres