Art and the Virtual: Post-Cinematics, Immersion, and Agency

by Patrick Lichty

Theorist Steven Shaviro argues that media society is entering a new era - that of the Post-Cinematic. In Post Cinematic Affect,[Shaviro, 2010] he also describes the change in which attends this shift away from cinema as ontological frame. In the mid 2010’s, the time of this writing, artistic production is being shaped by a McLuhan-istic imposition of new forms, aesthetics, and narrative by new forms of media as film gave way to television, and television gave way to digital and networked, interactive and immersive media. In addition, these shifts in affect, production and interest follow the flows of capital as Virtual and Augmented Realities are in vogue, and corporations like Facebook (Oculus) and HTC (Vive) sponsor artists to begin producing new work. So, at the moment of this version of the exhibition, Shaviro suggests the Post-Cinematic may be said to rest at the confluence of changing affective, formal, and economic situations.

Brenda Laurel, in her Medium.com article, What is Virtual Reality?,[Laurel, 2016] bristles at the opportunism inherent in a technological boom. Currently, everything that remotely resembles immersion is “VR”, much the same as cellular bandwidth is sold in “GB,” where I live, in Dubai. During the period when a technology is fashionable, marketers stretch definitions to label everything that remotely looks like the fad with its terms. To clarify the formal argument, Laurel describes a number of criteria for VR, including immersion, agency, the ability to move within virtual space, the possibility for narrative construction, and more. She also notes that under her criteria, 360-degree video, Virtual Worlds like Second Life, and even immersive environments like CAVEs fail the virtuality test.

While this may be true, broadening inclusion to virtual worlds, which are not immersive but describe virtuality, and not 360 video, which offer immersion, but do not allow agency, offer insights into the synthetic reality arts.

What Brenda Laurel describes in her essay, is that regardless of what virtuality, or augmentation is for that matter, it causes fundamental challenges for theorists, critics, artists, and curators. For that reason, I wish to take Quaranta’s “post-media” approach, [Quaranta, 2010] and discuss the conditions of virtuality, augmentation, and mixed reality as a set of situations and effects that are shaped by the affective, formal, and economic, although I will focus in the first two.

The distinction of immersive spaces in relation to the Post-Cinematic relates to why I would include virtual worlds in our Intermedial Venn diagram (after Higgins) and not 360-degree video. While 360-degree video fulfills the criteria of immersion and an ability to look around, that is where its claim to virtuality stops. In this form, one is not able to move around in the space, change the narrative, or interact (agency/action), and in this case, is clearly merely a form of interactive cinema. On the other hand, virtual worlds like Second Life, while rarely presenting total immersion (there is a browser that supports visitors), point toward it. And following Ramachandran’s argument for affective mirroring to the free-roaming avatar in its 3-dimensional space, I argue that we psychologically transfer into immersion and assume that avatar’s agency. For those reasons, I argue for virtual worlds and not 360-degree video for inclusion in my case for virtuality.

Louis Giannetti, in his seminal book Understanding Movies, [Giannetti, 2014] defines many formal aspects of cinema, but especially the fixity of point of view and the notion of audience. In the case of the immersive synthetic arts (“realities”), the notion of the fixed camera and audience as spectator vanishes into audience, morphing into the role of Director of Photography, traveling across the mediated terrain, or in the case of Augmented Reality, placing the mediated actors into physical space. In fact, space, and the making or recontextualization of place for aesthetic and conceptual purposes is a prime component in all reality practices. This spans across Virtuality, Augmentation, and hybrid spatial work. As I have written on virtual and augmented art, the modality of this (re)presentation of space, to go back to Naimark, is crucial. The first works, whether visor or spatially based, dealt primarily with the creation of and alt- or as B Coleman in Hello Avatar has termed, an “X-Space” [Coleman, 2011] that interfaces between the human interactor and the synthetic space in which they are situated.

The notion of situation of immersive synthetic space, whether it is a 3D projection in front of a stationary cyclist riding through a simulated textual city as with Shaw’s Legible City (1989) [Shaw, 1989] or a CAVE 3D projection room seemed to be the logical traditional space for virtual exploration. Oliver Grau, in his seminal book Virtual Art,[Grau, 2004] referred to Neolithic cave painting and Bacchic mystery rooms as early examples of immersive spaces. It would also be reasonable to follow through the later Second Millennial practices of Panorama, Diorama, and Cyclorama as precedents to inspire the coming of CAVEs, which project five walls around a user. In a way, this is the cybernetic Lascaux. In order for the human zeitgeist to understand synthetic space, it needs a physical backdrop onto which to model it. In this writer’s opinion, spaces like CAVEs create the reassuring scaffold of a physical room while introducing the virtual space beyond it. In many ways, this was the technocultural “Hello World” for the virtual.

Erin Manning explores the relations between motion and thought in Creative Propositions for Thought in Motion [Manning, 2008], where her examples of sensation, articulation, and expression as articulations of thought and ‘becoming’ denotes her belief that we think in space, and from physical spaces we begin the journey into the Virtual. For example, in the Earwax Production radio presentation Virtual Paradise, featuring Jaron Lanier, Brenda Laurel, and Terrence McKenna from the turn of the 1990’s, we hear McKenna say:

“So then, if I were in this VR environment or this electronic set-up that I’m envisioning, as I spoke to you over my shoulder, there would be, in space, a kind of tinker-toy like construction. In space, a kind of tinker-toy like construction, which would be rippling along under the rules of English grammar and the construction of my syntax.” [Earwax, 1993]

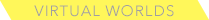

This is so reminiscent of the potential of CAVE-based space, and now systems like the VIVE with its killer app, the spatial paint program TiltBrush, that the re-situation of forms of virtuality from rooms to sensed spaces with visors and articulators over 20 years makes sense. It merely took that time form Jaron Lanier’s model of the visor to mature, conceptually and technologically. But from the 90’s to the ‘10’s, virtual worlds may be the incubators of virtual art.

To talk about Virtual and Augmented space, with Mixed Reality being a technologically extended pastiche of one or both as forms of Kaprow’s Happening, I return to Baudrillard, Bolter/Grusin, Naimark, and even Massumi and Debord and their ideas of Simulation, Remediation, (re)presentation, affect, and spectacle. Here I feel there is an epistemic thread running through these ideas through the progression in the history of Reality Art. To be more exact, this line of thought seems to have played itself out in the realm of virtual world art in the last ten years in the virtual world, Second Life.

Massumi: Virtuality and Affect

Brian Massumi, in Parables for the Virtual, [Massumi, 2002] discusses the causality of affect to emotion moving through the process of feeling. What is interesting about Massumi here is that affect in terms of the pre-perceptual; it is the initial impact that is felt and then processed to result in emotion. Affect is virtual, prepersonal; it is a feeling that is in the Deleuzian act of becoming, and this is important in terms of the post-cinematic. If we combine Massumi with the thought of V.J. Ramachandran in terms of human organisms transferring their emotions onto one another, especially through avatars as defined by the brain’s capacity for mirroring or remodeling the empathic, we arrive at many of the experiences inherent in VR and AR. As the user is given control of the camera, the mis-en-scene is always becoming; that is, the scenario is always new. And, if there is an avatar present, there is an affective connection to that avatar that creates a connection creating affective immersion and therefore, a synchronization of the human mind with the synthetic reality. This creates immersion, affective connection, phantasmagoria in the synthetic world playing into Debord’s notion of the spectacular and Baudrillard’s ideas of the mass mediascape and simulated culture.

Baudrillard: Simulations and Simulacra

In the early 1980’s, the foundations were being laid for Synthetic Reality culture with French pataphysician Jean Baudrillard’s Simulations and Simulacra [Postner, 1988] and William Gibson’s cyberpunk novel, Neuromancer.[Gibson, 1984] Gibson’s vision of being jacked onto a “consensual hallucination” would lead to Jaron Lanier’s next generation of Ivan Sutherland’s conception of the head mounted display (aka the “Sword of Damocles”). In the virtual world of philosophy, by late 1990’s Baudrillard had revealed a vision of a mediascape where mediated reality would become as legitimate as the physical, or even more so. But for the architects of virtual worlds, worlds like ActiveWorlds and Second Life became the basis of simulating galleries and art centers, testing creative space’s extension into the synthetic.

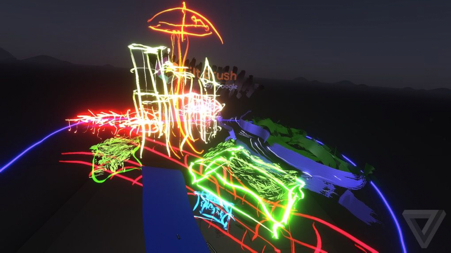

One of the earliest art spaces in an online world is Miltos Manetas’ Chelsea in ActiveWorlds. (2008-2011).[Manetas, 2008] A partnership for art and architecture in the ActiveWorlds online world between Manetas and Andreas Angelidakis. From Angelidakis’ website:

“Chelsea was a virtual city for art and architecture, a 3D community that included artists, curators, architects, institutions and galleries. It was a world that we put together with Miltos Manetas, to experience the new sense of place that the Internet was providing. Architecturally the challenge was to design buildings on the spot and in a way that they downloaded fast, and registered on the short attention span of the internet user. This produced buildings based on the existing Active Worlds 3D library, buildings that could register as quickly as a logo.” [Angelidakis]

Chelsea in ActiveWorlds,Image courtesy Andreas Angelidakis

This partnership was an initial expedition into virtual space testing the rules of quotidian space in online worlds. Goldin+Senneby’s artspace project, The Port,[Goldin+Senneby, The Port] was a Second Life art community initiated in 2004 in Stockholm in collaboration with architect Tor Lindstrand. During its height, it had over 50 members, and produced community led discussions and projects to investigate collaborative productions through relations of trust in a virtual environment. The project resulted in a Print on Demand book, Flack Attack! [Goldin+Senneby, Flack Attack!] and was featured on the Whitney Museum ArtPort site.[Paul, 2005] In this case, The Port had become as real as any physical space. These two spaces led to any number of notable online artspaces, like Ars Virtua, Odyssey, TenSquared, Eyebeam Island, DiMoDA, and RMB City, which will be noted in (re)presentation later in this essay. While this example of simulating artspaces are more likely considered conceptual works, the import is that these spaces illustrate the ability for virtuality to function as effectively as brick and mortar in light of synthetic realities.

Bolter/Grusin: Remediation

In the development of art in synthetic/syncretic realities, the next developmental step seems to be that of remediation. In Remediation: Understanding New Media,[Bolter and Grusin, 2000] Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin explore the translation of experience from one medium to another. While this shift creates formal changes in the message and experience, it also creates any number of glitches and errors when moving from one conceptual space to another. In Contemporary Art circles, this represented a shift in context when Marina Abramovic performed Seven Easy Pieces in 2005,[MoMA, 2016] where she took several seminal performance art works and resituated them in the atrium of the Guggenheim. In 2006, Eva and Franco Mattes created Reenactments,[Mattes, 2010] a series of recontextualized works from Abramovic, Gilbert and George, and Vito Acconci. This, in context with their Thirteen Most Beautiful Avatars (After Warhol),[Banovich, 2006] exposed the continuities and absurdities that occur when taking an embodied work out of its original context. This would be expanded upon by the Neo-Dadaist/FLUXUS group Second Front,[] who sought not to merely translate existing work, but generate new works specific to the space they inhabited. Where spaces like Chelsea and The Port sought to explore how virtual space worked in an art context, the Mattes, Gazira Babeli, and Second Front probed how we translated experience and context from one space to another.

Reenactments, Image Courtesy Eva and Franco Mattes

Naimark: (re)presentation

In Michael Naimark’s lecture, Thereness [Naimark, 2015] he discusses the relationship between image and space, disambiguation from cinema, verisimilitude and place. A good example of his would be the 3D panoramic video rotunda Be Now Here. Naimark explains that the creation of (re)mediated space depends on the re-presentation of the experience from its source to the technological space. This may seem like a mix between remediation and simulation, but I argue that it extends these both with the addition of gestalt; the “is-ness” of the work in the virtual.

(re)Presenting Beijing: Cao Fei’s RMB City

Cao Fei’s RMB City,[Guggenheim, 2008] a surreal four-server Second Life caricature of Beijing, launched in 2009 and lasting for about five years, transcended the notion of remediation in that it is such a pastiche of the original, only the “thereness” or gestalt, remains. The Imperial City, the Olympic Stadium, all exist alongside floating pandas and Duchampian bicycle wheels, none of which exist in the actual Beijing. Her conceptual project of selling “apartments” re-presented a cultural reality of Beijing, and its display in London’s Serpentine Gallery gave the implications of its existence at an art space and intersected virtual presence with physical credibility. And perhaps it is a surreal remediation, but there is a grossly mimetic quality that RMB City surpassed. It created space and implied its subject while not attempting to duplicate it.

Augmentation: Gesture and Overlay

Until now, this essay has dealt primarily with virtuality as the site of discussion for synthetic reality and the immersive arts. While Augmented Reality is also a subset of immersive synthetic reality, the fact that it overlays onto the interactor’s surrounding physical space means its experience is fundamentally different, both qualitatively and quantitatively. As I wrote in my essay, The Aesthetics of Liminality: Augmentation as an Art Form,[Lichty, 2014] I defined that the key difference between VR and AR is the manner in which the interactor access physical space through the gestural gaze. These “gestures” as I called them relate to the registration that the gaze maps between the retinal and the physical that have to do with whether the augment’s target is based on print, GPS, or even spatial and facial recognition. Whereas VR is concerned with the creation of space and the body that inhabits it, AR creates a doubling of space around the body and creates tensions between user, overlay, and subject. In addition, AR presents issues in regards to interaction with the overlay; the mobile screen is more traditional than the manual gesture of the Hololens or Meta. So, with the technical aspect of AR, the way the content is registered to the physical world, the way it is delivered to the interactor, and the way that interactor engages the content define AR art. Also, a recent addition to this dialogue is that devices like Hololens allow persistent content based only on spatial recognition – the AR sculptures of William Gibson’s Spook Country [Gibson, 2007] are now entirely feasible. Gibson’s trope of dead celebrities at the place and time of their death describes the notion of spatial context in Augmented Reality art.

As an artform, AR generally uses physical space as the context for virtual content. In the case of Skwarek et al’s Occupy AR, the fact that under US Law, no one can protest on private property excluded Occupy protesters from assembling in from of the Wall Street Stock Exchange. It does not mean that an AR artist cannot place geolocative art in front of that same place, placing contestational material in front of the site in question. Would Thiel and Pappenheimer’s skywriting AR piece have a different meaning when placed into a different contextual frame? As long as it addresses the environment that the augment-figure uses as a ground, this is an intrinsic formal aspect of the work, And when the figure includes physical or non-AR/VR works, one is confronted with the additional complexities of Mixed Reality.

Occupy AR: Image Courtesy Mark Skwarek

Bending Genres: Mixed Reality Art

When talking about AR and VR, the next proposition is to merge genres, such as Physical Computing, Dance, Sculpture, and so on with these forms. Because of the mutability of MR and the difficulty of categorizing this meta-genre, I will largely leave MR for my ongoing discussion of synthetic reality art. What is specific to it though, is constructions of space. Kaprow and the FLUXUS artists did this in creating Happenings and FLUXUS Performance, as well as Schwitters in creating his Merzbau. Mixed Reality can encompass computer vision, tele-present VR to “real space”.

A brief illustration of MR can be the creation of a life-sized two-way representational gate to Second Life (Y.Antoine)[Sascha, 2007] an opera incorporating AR fiducial markers (Hart),[Stock, 2014] or computer vision performatively manipulating particles overlaid onto actors (Levin).[Levin, 2003] MR refers to the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk (“Total work of art”) and Higgins’ Intermedial Art. The defining factor of MR is the creation of spaces that incorporate various modes of synthetic space.

From MR to Contemporary Conceptions of the Virtual

Where MR starts to re-merge with genres like VR can be seen in popular culture. Musion’s large scale “holograms” [Machkovech, 2016] like Virtual Tupac and Miku Hatsune have featured Japanese monster-sized real-time representations of these artists to much attention. The culture surrounding Miku Hatsune is a massive one and is documented in my essay The Translation of Art in Virtual Worlds. It has resulted in records, concerts, tools to make one’s own Miku animations, as well as video games and AR that allow fans to “live” with Miku in their apartment. With the popularity of synthetic idols, much like Rei Toei from William Gibson’s Idoru [Gibson, 2011], the notion of synthetic reality deeply insinuates itself into the physical.

This merger of MR as a representation of VR and the “reality” of the avatar as personality, has led to the artist as avatar. In a 2016 interview,[Ellis-Petersen, 2016] Bjork appeared as a synthetic being driven by motion capture technology at an exhibition at London’s Somerset House. In other venues, Transmediale 2016 featured artists without a “real world” referent, like Miku Hatsune and Laturbo Avedon, following in the tradition of other avatar artists like Gazira Babeli in the mid-2000’s, or the virtual troll NN/Antiorp in the 1990’s [Lovink, 2004]. The synthetic artist in the gallery and festival is thus a Cao Fei-like boomerang of virtuality into physical culture. This is also seen in Salazar-Caro and Robertson’s Digital Museum of Digital Art,[Palop 2015] which locates a VR-based gallery back into the brick and mortar milieu. In the case of Rettberg, et al’s Hearts and Minds,[Coover, et al, 2016] a stereoscopic VR narrative that allows the interactor to enter the spaces of and hear stories about the atrocities experienced and committed by four American soldiers during the Iraq War. But lastly, there are works like Hentschlager’s Zee and Sol where the use of media and space are loaded (light, sound, fog, media) to the point where physical and media disappear, and this is likely the sought after gesamtkunstwerk in reality arts. This play with spatial modality appears to represent the incursion of synthetic reality art practice in the contemporary as of 2016.

When considering the formal trajectory of synthetic reality art from VR to AR to Mixed Reality and onto the translations into physical and Contemporary art spaces, the set of practices stemming from a post cinematic interactive tradition have morphed and infiltrated one another. What is common to them is the generation of synthetic realities and integrating them into a sense of space, conferring agency to the viewer, and forms of more or less immersion. For the Real-Fake exhibition reboot, the interest is how synthetic praxis, as symptom of the techno-culture’s regimes of power, emerge in New Media and Contemporary art in increasingly complex and cross-pollinating ways. When dealing with technology dedicated to the re-creation and re-presentation and fracturing of space, the art that comes from it will continue to (re)present the simulated world and how we immerse ourselves in the myths we have almost always synthesized about reality.

REFERENCES:

Angelidakis, Andreas. "Chelsea in ActiveWorlds." This Is Angelidakis.com. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.angelidakis.com/_PAGES/Chelsea.htm.

Banovich, Tamas. "Eva & Franco Mattes - Thirteen Most Beautiful Avatars." Eva & Franco Mattes. 2006. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.postmastersart.com/archive/01org_07/01org_07_window1.html.

Bolter, Jay David., and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2000.

Coleman, Beth. Hello Avatar: Rise of the Networked Generation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011.

Coover, Roderick, Arthur Nishimoto, Scott Rettberg, and Daria Tsoupikova. “Hearts and Minds: The Interrogations Project. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.crchange.net/hearts-and-minds/.

Earwax Productions (Jim McKee and Barney Jones) and David Lawrence, Virtual Paradise, Radio, 1993

Ellis-Petersen, Hannah. "Björk: 'I Build Bridges between Tech and the Human Things We Do'" The Guardian. August 31, 2016. Accessed October 29, 2016.https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/aug/31/bjork-build-bridges-technology-somerset-house-london-virtual-reality-vulnicura

Gaskins, Nettrice. "Performative Interventions: The Progression of 4D Art in a Virtual 3D World | ART21 Magazine." ART21 Magazine. December 31, 2009. Accessed October 29, 2016.http://blog.art21.org/2009/12/31/performative-interventions-the-progression-of-4d-art-in-a-virtual-3d-world/#.WBRNcuF97wc.

Giannetti, Louis D. Understanding Movies. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2014.

Gibson, William. Idoru. S.l.: Penguin Books, 2011.

Gibson, William. Neuromancer. New York: Ace Books, 1984.

Gibson, William. Spook Country. London: Viking, 2007.

"Goldin+Senneby » Blog Archive » The Port." Goldin+Senneby » Blog Archive » The Port. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.goldinsenneby.com/gs/?p=62.

"Goldin+Senneby » Blog Archive » Flack Attack." Goldin+Senneby » Blog Archive » Flack Attack. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.goldinsenneby.com/gs/?p=822.

Grau, Oliver. Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2004.

Laurel, Brenda. "What Is Virtual Reality?" Medium.com. June 15, 2016. Accessed October 29, 2016. https://medium.com/@blaurel/what-is-virtual-reality-77b876d829ba.

Guggenheim Museum, "RMB City: A Second Life City Planning by China Tracy (aka: Cao Fei)." October 26, 2016. Accessed October 29, 2016. https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/23251.

Laurel, Brenda. Computers as Theatre. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Pub., 1991

Levin, Golan. Messa Di Voce (Performance). 2003. Accessed October 29, 2016.

http://www.flong.com/projects/messa/.

Lichty, P. "The Aesthetics of Liminality: Augmentation as an Art Form." In Augmented Reality Art: From an Emerging Technology to a Novel Creative Medium, edited by Vladimir Geroimenko. Springer/Verlag, 2015.

Lichty P. “The translation of art in virtual worlds.” In: Grimshaw M, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Virtuality. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014a

Lovink, Geert. My First Recession: Critical Internet Culture in Transition, V2 Publishing, Rotterdam, 2003

Machkovech, Sam. "Review: Japanese Hologram Pop Star Hatsune Miku Tours North America." Ars Technica. April 29, 2016. Accessed October 29, 2016.http://arstechnica.com/the-multiverse/2016/04/waving-glow-sticks-at-hologram-anime-pop-stars-our-night-with-hatsune-miku/.

Manetas, Miltos. "VIRTUAL WORLDS: CHELSEA IN ACTIVE WORLDS." VIRTUAL WORLDS: CHELSEA IN ACTIVE WORLDS - Manetas. Accessed October 29, 2016.http://miltosmanetas.com/filter/Life/VIRTUAL-WORLDS-CHELSEA-IN-ACTIVE-WORLDS.

Manning, Erin. "Inflexions 1: Creative Propositions for Thought in Motion by Erin Manning." Inflexions 1: Creative Propositions for Thought in Motion by Erin Manning. May 2008. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.inflexions.org/n1_manninghtml.html

Massumi, Brian. "Parables for the Virtual | Duke University Press." Parables for the Virtual | Duke University Press. 2002

Mattes, Franco & Eva. "Reenactments (2007-10)." Reenactments (2007-10). 2010. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://0100101110101101.org/reenactments/.

"Marina Abramovic – Seven Easy Pieces." The Museum of Modern Art. Accessed October 29, 2016. https://www.moma.org/explore/multimedia/audios/190/1998.

Naimark, Michael. "Thereness: On Place And Virtual Reality." Designers + Geeks. September 17, 2015. Accessed October 29, 2016. https://designersandgeeks.com/events/thereness.

Palop, Benoit. "Move Over Louvre, The DiMoDa Museum Exists Online in VR and IRL | The Creators Project." The Creators Project. November 6, 2015. Accessed October 29, 2016.http://thecreatorsproject.vice.com/blog/dimoda-is-a-digital-museum-of-digital-art.

Paul, Christiane. "Whitney Artport: Gate Pages December 05: Simon Goldin & Jakob Senneby." Whitney Artport: Gate Pages December 05: Simon Goldin & Jakob Senneby. 2005. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://artport.whitney.org/gatepages/december05.shtml.

Postner, Mark. Jean Baudrillard: Selected Writings. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1988.

Stock, Jennifer. "Sculptural Opera: Claudia Hart's Alices (Walking) at EyeBeam." I CARE IF YOU LISTEN. April 02, 2014. Accessed October 29, 2016. https://www.icareifyoulisten.com/2014/04/claudia-hart-alices-walking-eyebeam/.

Quaranta, Domenico. Media, New Media, Postmedia. Milano: Postmedia Books, 2010.

Sascha. "IMAL Opening." We Make Money Not Art. October 08, 2007. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://we-make-money-not-art.com/imal_opening/.

Shaviro, Steven. Post Cinematic Affect. Winchester, UK: 2010. Print.

"Legible City." Jeffrey Shaw Compendium. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.jeffreyshawcompendium.com/portfolio/legible-city/.

Angelidakis, Andreas. "Chelsea in ActiveWorlds." This Is Angelidakis.com. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.angelidakis.com/_PAGES/Chelsea.htm.

Banovich, Tamas. "Eva & Franco Mattes - Thirteen Most Beautiful Avatars." Eva & Franco Mattes. 2006. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.postmastersart.com/archive/01org_07/01org_07_window1.html.

Bolter, Jay David., and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2000.

Coleman, Beth. Hello Avatar: Rise of the Networked Generation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011.

Coover, Roderick, Arthur Nishimoto, Scott Rettberg, and Daria Tsoupikova. “Hearts and Minds: The Interrogations Project. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.crchange.net/hearts-and-minds/.

Earwax Productions (Jim McKee and Barney Jones) and David Lawrence, Virtual Paradise, Radio, 1993

Ellis-Petersen, Hannah. "Björk: 'I Build Bridges between Tech and the Human Things We Do'" The Guardian. August 31, 2016. Accessed October 29, 2016.https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/aug/31/bjork-build-bridges-technology-somerset-house-london-virtual-reality-vulnicura

Gaskins, Nettrice. "Performative Interventions: The Progression of 4D Art in a Virtual 3D World | ART21 Magazine." ART21 Magazine. December 31, 2009. Accessed October 29, 2016.http://blog.art21.org/2009/12/31/performative-interventions-the-progression-of-4d-art-in-a-virtual-3d-world/#.WBRNcuF97wc.

Giannetti, Louis D. Understanding Movies. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2014.

Gibson, William. Idoru. S.l.: Penguin Books, 2011.

Gibson, William. Neuromancer. New York: Ace Books, 1984.

Gibson, William. Spook Country. London: Viking, 2007.

"Goldin+Senneby » Blog Archive » The Port." Goldin+Senneby » Blog Archive » The Port. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.goldinsenneby.com/gs/?p=62.

"Goldin+Senneby » Blog Archive » Flack Attack." Goldin+Senneby » Blog Archive » Flack Attack. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.goldinsenneby.com/gs/?p=822.

Grau, Oliver. Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2004.

Laurel, Brenda. "What Is Virtual Reality?" Medium.com. June 15, 2016. Accessed October 29, 2016. https://medium.com/@blaurel/what-is-virtual-reality-77b876d829ba.

Guggenheim Museum, "RMB City: A Second Life City Planning by China Tracy (aka: Cao Fei)." October 26, 2016. Accessed October 29, 2016. https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/23251.

Laurel, Brenda. Computers as Theatre. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Pub., 1991

Levin, Golan. Messa Di Voce (Performance). 2003. Accessed October 29, 2016.

http://www.flong.com/projects/messa/.

Lichty, P. "The Aesthetics of Liminality: Augmentation as an Art Form." In Augmented Reality Art: From an Emerging Technology to a Novel Creative Medium, edited by Vladimir Geroimenko. Springer/Verlag, 2015.

Lichty P. “The translation of art in virtual worlds.” In: Grimshaw M, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Virtuality. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014a

Lovink, Geert. My First Recession: Critical Internet Culture in Transition, V2 Publishing, Rotterdam, 2003

Machkovech, Sam. "Review: Japanese Hologram Pop Star Hatsune Miku Tours North America." Ars Technica. April 29, 2016. Accessed October 29, 2016.http://arstechnica.com/the-multiverse/2016/04/waving-glow-sticks-at-hologram-anime-pop-stars-our-night-with-hatsune-miku/.

Manetas, Miltos. "VIRTUAL WORLDS: CHELSEA IN ACTIVE WORLDS." VIRTUAL WORLDS: CHELSEA IN ACTIVE WORLDS - Manetas. Accessed October 29, 2016.http://miltosmanetas.com/filter/Life/VIRTUAL-WORLDS-CHELSEA-IN-ACTIVE-WORLDS.

Manning, Erin. "Inflexions 1: Creative Propositions for Thought in Motion by Erin Manning." Inflexions 1: Creative Propositions for Thought in Motion by Erin Manning. May 2008. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.inflexions.org/n1_manninghtml.html

Massumi, Brian. "Parables for the Virtual | Duke University Press." Parables for the Virtual | Duke University Press. 2002

Mattes, Franco & Eva. "Reenactments (2007-10)." Reenactments (2007-10). 2010. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://0100101110101101.org/reenactments/.

"Marina Abramovic – Seven Easy Pieces." The Museum of Modern Art. Accessed October 29, 2016. https://www.moma.org/explore/multimedia/audios/190/1998.

Naimark, Michael. "Thereness: On Place And Virtual Reality." Designers + Geeks. September 17, 2015. Accessed October 29, 2016. https://designersandgeeks.com/events/thereness.

Palop, Benoit. "Move Over Louvre, The DiMoDa Museum Exists Online in VR and IRL | The Creators Project." The Creators Project. November 6, 2015. Accessed October 29, 2016.http://thecreatorsproject.vice.com/blog/dimoda-is-a-digital-museum-of-digital-art.

Paul, Christiane. "Whitney Artport: Gate Pages December 05: Simon Goldin & Jakob Senneby." Whitney Artport: Gate Pages December 05: Simon Goldin & Jakob Senneby. 2005. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://artport.whitney.org/gatepages/december05.shtml.

Postner, Mark. Jean Baudrillard: Selected Writings. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1988.

Stock, Jennifer. "Sculptural Opera: Claudia Hart's Alices (Walking) at EyeBeam." I CARE IF YOU LISTEN. April 02, 2014. Accessed October 29, 2016. https://www.icareifyoulisten.com/2014/04/claudia-hart-alices-walking-eyebeam/.

Quaranta, Domenico. Media, New Media, Postmedia. Milano: Postmedia Books, 2010.

Sascha. "IMAL Opening." We Make Money Not Art. October 08, 2007. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://we-make-money-not-art.com/imal_opening/.

Shaviro, Steven. Post Cinematic Affect. Winchester, UK: 2010. Print.

"Legible City." Jeffrey Shaw Compendium. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.jeffreyshawcompendium.com/portfolio/legible-city/.